Oswald Bastable and Others Read online

Page 11

BILLY AND WILLIAM

A HISTORICAL TALE FOR THE YOUNG

'_Have you found your prize essay?_' '_No; but I have found the bicycle of the butcher's boy._'

It is rather trying to have to walk three miles to the station, to saynothing of the three miles back, to meet a cousin you have never seenand never wish to see, especially if you have to leave a kite half made,and there is no proper lock to the shed you are making your kite in.

The road was flat and dusty, the sun felt much too warm on his back, thehill to the station was long and steep, and the train was nearly an hourlate, because it was a train on the South-Eastern Railway. So Williamwas exceedingly cross, and he would have been crosser still if he couldhave known that I should ever call him William, for though that happenedto be his name, the one he 'answered to' (as the stolen-dogadvertisements say) was 'Billy.' So perhaps it would be kind of me tospeak of him as Billy, because it is rather horrid to do things you knowpeople won't like, even if you think they'll never know you've donethem.

Well, the train came in, and it was annoying to Billy, very, that fouror five boys should bundle out of the train, and he should have to go upto them one after the other and say:

'I say, is your name Harold St. Leger?'

He did not particularly like the look of any of the boys, and of courseit happened that the very last one he spoke to was Harold, and that hewas also the one whom Billy liked least particularly of the whole lot.

'Oh, you are, are you?' was all he could find to say when Harold hadblushingly owned to his name. Then in manly tones Billy gave the orderabout Harold's luggage and the carrier, said 'Come along!' and Haroldcame.

Harold was a fattish boy with whitey-brown hair, and he was as soft andwhite as a silkworm. Billy did not admire him. He himself was hard andbrown, with thin arms and legs and joints like the lumps of clay onbranches that the gardener has grafted. And Harold did not admire _him_.

There was little conversation on the way home; when you don't want tohave a visitor and he doesn't want to be one, talking is not much fun.When they got home there was tea. Billy's mother talked politely toHarold, but that did not make anyone any happier. Then Billy took hiscousin round and showed him the farm and the stock, and Harold was lessinterested than you would think a boy could be. At last, weary of tryingto behave nicely, Billy said:

'I suppose there must be _something_ you like, however much of a muffyou are. Well, you can jolly well find it out for yourself. I'm going tofinish my kite.'

The silkworm-soft face of Harold lighted up.

'Oh, _I_ can make kites,' he said; 'I've invented a new kind. I'll helpyou if you'll let me.'

Harold, eager, quick fingered, skilful, in the shed among the string,and the glue, and the paper, and the bendable, breakable laths, wasquite a different person from Harold, nervous and dull, among thefarmyard beasts. Billy allowed him to help with the kite, and he beganto respect his cousin a little more.

'Though it's rather like a girl, being so neat with your fingers,' hesaid disparagingly.

'I wish I'd got the proper sort of paper,' Harold said, 'then I'd makemy new patent kite that I've invented; but it's a very extra sort ofkind of paper. I got some once at a butter-shop in Bermondsey, but thatwas in a dream.'

Billy stared.

'You must be off your chump,' he said; and he felt more sorry than everthat his jolly country holiday was to be spoiled by a strange cousin,who ought, perhaps, to be in a lunatic asylum rather than at arespectable farm.

That night Billy was awakened from the dreamless sleep which blesses thesort of boy he was to find Harold excitedly thumping him on the backwith a roll of stiff paper.

'Wake up,' he said--'wake up! I _will_ tell somebody that's awake. Idreamed that a jackdaw came in and flew off with that thin paper thingthat was on the chest of drawers with the gilt button at the corner, andthen I dreamed I got up and found this roll of paper up the chimney. Andwhen I woke up I found _it_ had and _I_ had, and it's the real rightkite-paper for my patent kite--just like I dreamed I bought in thebutter-shop in Bermondsey. And it's five o'clock by the church clock,and it's quite light. I'm going to get up directly minute and make mypatent kite.'

'Patent fiddlestick!' replied Billy, sleepy and indignant. 'You getalong and leave me be; you've been dreaming, that's all. Just like agirl!'

'Yes,' repeated Harold gently, 'I _have_ been dreaming; but when I wokeup I found _it_ had and _I_ had; and here's the paper, and the flimsything with the gold stud's _gone_. You get up and see----'

Billy did. He got up with a bound, and he saw with an eye. And Williamturned on Harold and shook him till his teeth nearly rattled in his headand his pale eyes nearly dropped out. (I have called him William herebecause I really think he deserves it. It is a cowardly thing to shake acousin, even if you do not happen to be pleased with him.)

'Wha--wha--what's the matter?' choked the wretched Harold.

'Why, you miserable little idiot, you've _not_ been dreaming at all!You've been lying like a silly log, and letting that beastly bird carryoff my prize essay! That's _all_! And it took me ten days to do, and Ihad to get almost all of it out of books, and the worse swat I ever didin my life. And now it's all no good. And there aren't any books downhere to do it again out of. Oh, bother, _bother_, BOTHER!'

'I'm very sorry for you,' said Harold, 'but I didn't lie like logs--Idid dream--and I've got the kite-paper, and I'll help you write theessay again if you like.'

'I shouldn't be surprised if it was all a make-up,' said William. (I_must_ go on calling him William at present.) 'You've hidden the essayso as to be able to send it in yourself.'

'Oh, how _can_ you?' said Harold; and he turned pale just like a girl,and just like a girl he began to cry.

'Now, look here,' the enraged William went on, 'I've got to be civil toyou before people; but don't you dare to speak to me when we're alone.You're either a silly idiot or a sneaking hound, and either way I'm notgoing to have anything to do with you.'

I don't know how he could have done it, but William kept his word, andfor three days he only spoke to Harold when other people were about.This was horrible for Harold; he had been used to being his father'spride and his mother's joy, and now he was Nobody's Anything, which isthe saddest thing in the world to be. He tried to console himself bymaking kites all day long, but even kites cannot comfort you when nobodyloves you, and when you feel that it really is not your fault at all.

William went about his own affairs; he was not at all happy. He finishedhis kite and flew it, and he lost it because the string caught on thechurch weather-cock, which cut it in two. And he tried to rewrite hisprize essay, but he couldn't, because he had taken all the stuffing forit out of books and not out of his head, where it ought to have been.

Harold found some moments of forgetfulness when he was making the patentkite. It was very big, and the roll of paper he had found in his dreamin the chimney was exactly the right thing for patent kite-making. Butwhen it was done, what was the good? There was no one to see him fly it.He did fly it, and it was perfect. It was shaped like a bird, and itrose up, and up, and up, and hung poised above the church-tower, lightand steady as a hawk poised above its prey. William wouldn't even comeout to look at it, though Harold begged him to.

The next morning Harold dreamed that he had not been able to bear thingsany longer, and had run away, and when William woke up Harold was gone.Then William remembered how Harold had offered to help him with hiskite, and would have helped him to rewrite the essay, and how throughthose three cruel days Harold had again and again tried to make friends,and how, after all, he was with his own people, and Harold was astranger.

He said, 'Oh, bother, I wish I hadn't!' and he felt that he had been abeast. This is called Remorse. Then he said, 'I'll find him, and I'll beas decent to him as I can, poor chap! though he _is_ silly.' This iscalled Repentance.

Then he found a letter on Harold's bed. It said (and it was blotted withtears, and it had a blob of glue on it)

:

'DEAR BILLY,

'It wasn't my fault about your essay, and I'm sorry, and am going to run away to India to find my people. I shall go disguised as a stowaway.

'Your affectionate cousin,

'HAROLD EGBERT DARWIN ST. LEGER.'

Billy did not have to show this letter to his mother, because she hadgone away for the day, so he did not have to explain to her what abeast he had been. If he had had to do this, it would have been part ofwhat is called Expiation.

Then he got the farm men to go out in every direction, furnished with afull description of Harold's silkworm-like appearance, and Billyborrowed a bicycle from a noble-hearted butcher's boy in the village andset out for Plymouth, because that seemed the likeliest place to look infor a cousin who was running away disguised as a stowaway. The wind blewstraight towards the sea, and it occurred to Billy--he deserves to becalled Billy now, I think--that the great patent kite, which was tenfeet high, would drag him along like winking if he could only set itflying, and then tie it to the handle-bar of the bicycle. It was rathera ticklish business to get the kite up, but the butcher's boy helped--hehad a noble heart--and at last it was done. Billy saw the greatbird-kite flying off towards Plymouth. He hastily knotted the string tothe bicycle handle, held the slack of it in his hand, mounted, started,paid out the slack of the string, and the next moment the string wastight, and the kite was pulling Billy and the bicycle along thePlymouth road at the rate of goodness-only-knows-how-improbably manymiles an hour.

At last he came to the outskirts of Plymouth. I shall not tell you whatPlymouth was like, because Billy did not notice or know at all what itwas like, and there is no reason why you should. Plymouth seemed toBilly very much like other places. The only odd thing was that he couldnot stop his bicycle, though he pulled in the kite string as hard as hecould. He flew through the town. All the traffic stopped to let himsteer his mad-paced machine through the streets, and tradespeople, andpeople walking on business, and people walking for pleasure, all stoppedwith their respectable mouths wide open to stare at Billy on hisbicycle. And the kite pulled the machine on and on without pause, and ata furious rate, and Billy, in despair, was just feeling in his pocketfor his knife to cut the string, when some mighty sky-wind seemed tocatch the kite, and it gave a leap and went twenty times as fast as ithad gone before, and the bicycle had to go twenty times as fast too, andbefore Billy could say 'Jack Robinson,' or even 'J. R.,' for short, thekite rushed wildly out to sea, dragging the bicycle after it, right slapoff the edge of England. So Billy and the butcher's boy's bicycle weredragged into the sea? Not at all. They were dragged _on_ to the sea,which is not at all the same sort of thing. For the kite was such a veryextra patent one, and so perfectly designed and made, that it was juststrong enough to bear the weight of Billy and the bicycle, and to keepthem out of the water. So that Billy found himself riding splendidlyover the waves, and there was no more splashing than there would havebeen on the road on a very muddy day. Luckily, the sea was smooth, or Idon't know what would have happened. It was smooth and greeny-blue, andthe sun made diamond sparkles on it, and Billy felt as grand as grand tobe riding over such a glorious floor. It was a fine time, but rather ananxious one too. Because, suppose the string had not held? No one couldpossibly ride a bicycle on the sea unless they had the really only trulyright sort of kite to hold the machine up.

Away and away went the kite, through the blue air up above, and away andaway went the bicycle over the greeny, foamy sea down below, and awayand away went Billy, and the kite went faster and faster and faster, andfaster went the bicycle--much, much faster than you would believeunless you had seen it as Billy did. And just at the front-door of theBay of Biscay the bicycle caught up with a P. and O. steamer, and thekite followed the course of the ship, and went alongside of it, so youcan guess how fast the bicycle was going.

And the Captain of the ship hailed Billy through a speaking-trumpet, andsaid:

'Ahoy, there!'

Billy replied:

'Ahoy yourself!'

But the Captain couldn't hear him. So the Captain said something thatBilly couldn't hear either. But the people who were meant to hear heard,and the great ship stopped, and Billy rode close up to it, and theyhauled him up by the string of the kite, and they put the bicycle in asafe place, and tied the string to the mast, and then the Captain said:

'I suppose I'm dreaming you, boy, because what you're doing isimpossible.'

'I know it is,' said Billy; 'only I'm doing it--at least, I was till youstopped me.'

They were both wrong, because, of course, if it had been impossible,Billy could not have done it; but neither of them had a scientificmind, as you and I have, dear reader.

So the Captain asked Billy to dinner, which was very nice, only therewas an uncertain feeling about it. And when Billy had had dinner, hesaid to the Captain:

'I must be going.'

'Is there nothing I can do for you?' said the Captain.

'I don't know,' said Billy, 'unless you happen to have a boy namedHarold Egbert Darwin St. Leger on board. He said he was going away in aship to India, disguised as a stowaway.'

The Captain at once ordered the ship to be searched for a boy of thisname in this disguise. The crew looked in the hold, and in the galley,and in the foretop, and on the quarter, and in the gaff, and the jib,and the topsail, and the boom, but they could not find Harold. Theyransacked the cross-trees, and the engine-room, and the bowsprit; theyexplored the backstays, the stays, and the waist, but they found nostowaway. They examined truck and block, they hunted through everyporthole, they left not an inch of the ribs unexplored; but no Harold.He was not in any of the belaying-pins or dead-eyes, nor was he hiddenin the capstan or the compass. At last, in despair, the Captain thoughtof looking in the cabins, and in one of them, hidden under the scatteredpyjamas and embroidered socks of a Major of Artillery, they foundHarold.

He and Billy explained everything to each other, and shook hands, andthere was not a dry eye in the ship. (Did you ever see a dry eye? Ithink it would look rather nasty.)

Then said Billy to Harold:

'This is all very well, but how am I to get you home?'

'I can ride on the step of the bike,' said Harold.

'But the wind won't take us back,' said Billy; 'it's dead against us.'

'Excuse me,' said the Captain in a manly manner; 'you know thatBritannia rules the waves and controls the elements. Allow me onemoment.'

He sent for the boatswain and bade him whistle for a wind, expresslystating what kind of wind was needed.

And everyone saw with delight, but with little surprise, the kitedeliberately turn round and retrace its steps towards the cliffs ofAlbion.

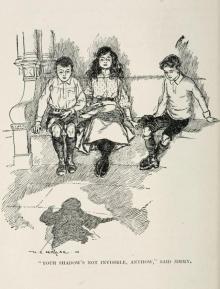

'The bicycle started, Billy in the saddle and Harold onthe step.'--Page 165.]

A cheer rose from passengers and crew alike as the bicycle was loweredto the waves, the string tightened, and the bicycle started, Billy inthe saddle and Harold on the step. The event was a perfect windfall tothe passengers. It gave them something to talk of all the way to Suez;some of them are talking about it still.

The kite went back even faster than it had come; it pulled the bicyclebehind it as easily as a child pulls a cotton-reel along the floor by abit of thread. So that Harold and Billy were home by tea-time, and itwas the jolliest meal either of them had ever had.

They had determined to stop the bicycle by cutting the string, and thenHarold would have lost the patent kite, which would have been a pity.But, most happily, the string of the kite caught in the vane on the topof the church tower, and the bicycle stopped by itself exactly oppositethe butcher's boy to whom it belonged. He had a noble heart, and he wasvery glad to see his bicycle again.

After tea the boys went up the church tower to get the kite; and I don'tsuppose you will believe me when I tell you that there, in the niche ofa window of the belfry, was a jackdaw's nest, and in it the HistoricalEssay which the jackdaw had stolen, as you will have guessed, for thesake of the br

ight gilt manuscript fastener in the corner.

And now Harold and Billy became really chums, in spite of all thequalities which they could not help disliking in each other. Each foundsome things in the other that he didn't dislike so very much, after all.

When Harold grows up he will sell many patent kites, and we shall all beable to ride bicycles on the sea.

Billy sent in his essay, but he did not get the prize; so it wouldn'thave mattered if it had never been found, only I am glad it was found.

I hope you will not think that this is a made-up story. It is verynearly as true as any of the history in Billy's essay that didn't get aprize. The only thing I can't quite believe myself is about the roll ofthe right kind of paper being in the chimney; but Harold couldn't thinkof anything else to dream about, and the most fortunate accidents dohappen sometimes even in stories.

The Magic World

The Magic World In the Dark

In the Dark The Enchanted Castle

The Enchanted Castle The Phoenix and the Carpet

The Phoenix and the Carpet The Magic City

The Magic City The Story of the Amulet

The Story of the Amulet The Wouldbegoods: Being the Further Adventures of the Treasure Seekers

The Wouldbegoods: Being the Further Adventures of the Treasure Seekers The Railway Children

The Railway Children The Diamond Lens

The Diamond Lens Fairy Tales for Young Readers

Fairy Tales for Young Readers Shakespeare's Stories for Young Readers (Dover Children's Classics)

Shakespeare's Stories for Young Readers (Dover Children's Classics) The Wouldbegoods

The Wouldbegoods The Incredible Honeymoon

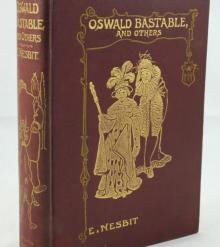

The Incredible Honeymoon Oswald Bastable and Others

Oswald Bastable and Others Pussy and Doggy Tales

Pussy and Doggy Tales New Treasure Seekers; Or, The Bastable Children in Search of a Fortune

New Treasure Seekers; Or, The Bastable Children in Search of a Fortune Five Children and It

Five Children and It Harding's luck

Harding's luck The Story of the Treasure Seekers

The Story of the Treasure Seekers The E. Nesbit Megapack: 26 Classic Novels and Stories

The E. Nesbit Megapack: 26 Classic Novels and Stories Shakespeare's Stories for Young Readers

Shakespeare's Stories for Young Readers