The Magic World

The Magic World In the Dark

In the Dark The Enchanted Castle

The Enchanted Castle The Phoenix and the Carpet

The Phoenix and the Carpet The Magic City

The Magic City The Story of the Amulet

The Story of the Amulet The Wouldbegoods: Being the Further Adventures of the Treasure Seekers

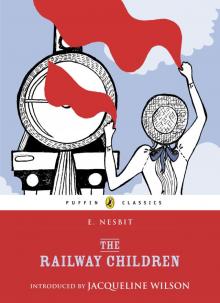

The Wouldbegoods: Being the Further Adventures of the Treasure Seekers The Railway Children

The Railway Children The Diamond Lens

The Diamond Lens Fairy Tales for Young Readers

Fairy Tales for Young Readers Shakespeare's Stories for Young Readers (Dover Children's Classics)

Shakespeare's Stories for Young Readers (Dover Children's Classics) The Wouldbegoods

The Wouldbegoods The Incredible Honeymoon

The Incredible Honeymoon Oswald Bastable and Others

Oswald Bastable and Others Pussy and Doggy Tales

Pussy and Doggy Tales New Treasure Seekers; Or, The Bastable Children in Search of a Fortune

New Treasure Seekers; Or, The Bastable Children in Search of a Fortune Five Children and It

Five Children and It Harding's luck

Harding's luck The Story of the Treasure Seekers

The Story of the Treasure Seekers The E. Nesbit Megapack: 26 Classic Novels and Stories

The E. Nesbit Megapack: 26 Classic Novels and Stories Shakespeare's Stories for Young Readers

Shakespeare's Stories for Young Readers